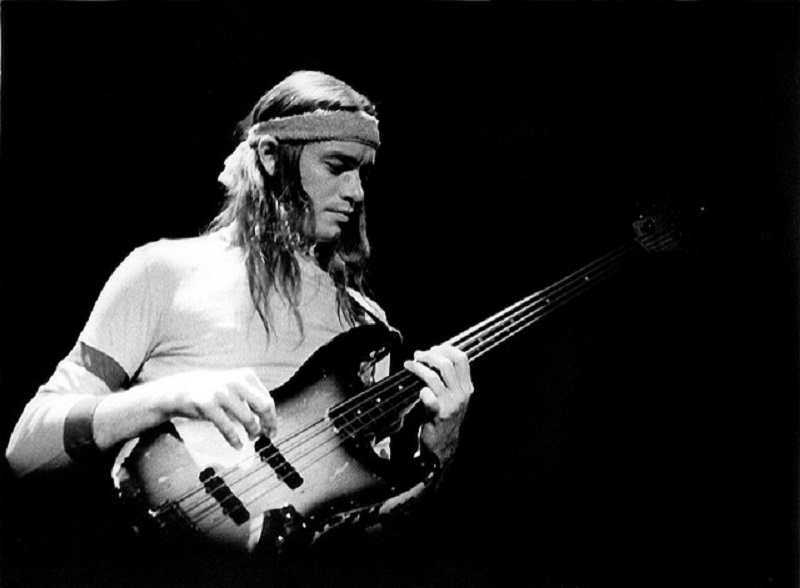

September 2017 marked 30 years since the untimely death of Jaco Pastorius, the self-proclaimed ‘greatest bass player of all time’ who completely revolutionised not only the instrument itself but also the way that it was played – Jaco pioneered the fretless bass and helped to make the electric bass a more legitimate jazz instrument (this may or may not be a terrible thing, depending on your point of view).

So why is everyone still talking about Jaco 30 years after his death? The fact is that he has influenced every single prominent electric bass player that has come through in the ‘post-jaco’ era; it doesn’t matter who you’re into – Pino Palladino, Mark King, Me’Shell N’degeocello, Gary Willis, John Patitucci, Marcus Miller, Will Lee, Richard Bona, Flea, Laurence Cottle, Stu Hamm – all of these great players have stolen a ton of stuff from Jaco. In fact, even if you’re keen on more modern players then Jaco is still relevant, as his influence can be clearly heard in the playing of Evan Marien, Joe Dart (Vulfpeck), Michael League (Snarky Puppy) and Hadrien Feraud.

What made Jaco So Great?

In order to understand why Jaco’s playing had such a profound impact on the history of the instrument we’re going to dig into his first commercial recording as a sideman, R&B guitarist Little Beaver’s ‘I Can Dig It Baby’, which was released in 1974, before Jaco’s infamous debut solo record, his appearance on Pat Metheny’s ‘Bright Size Life’ or Weather Report’s ‘Black Market’.

You can find a pdf of the transcription HERE

This wasn’t Jaco’s first recorded outing as such, he appeared on a record released under Paul Bley’s improvising artists label, originally titled Pastorius/Metheny/Ditmas/Bley (now widely referred to as ‘Jaco’) on which he can be heard playing some utterly ridiculous things in a not particularly accessible electronic free jazz setting. ‘I Can Dig It Baby’ represents Jaco’s first recording that would reach the ears of most mainstream listeners and allows us to study the key elements of his unique style in the context of a 6 minute pop song.

The credit for bass on ‘I Can Dig It Baby’ went to Nelson ‘Jocko’ Padron, but after a handful of notes it’s clear who’s in charge of the low end. What is most significant about Jaco’s recording debut is that it clearly demonstrates that he was a fully formed musician with a unique voice at the age of 22 or 23, which is an extremely rare thing. By examining the transcription of Jaco’s part on ‘I Can Dig It Baby’ we can isolate the fundamental elements of his style that would become so influential in years to come – it’s as if Jaco left us clues as to what he was going to unleash in the future as his career progressed.

5 essential ‘Jaco-isms’

1. Outlining Chords Using Harmonics

Bar 2 of the tune (Jaco’s fourth note of the piece) features a double stop harmonic which outlines the Bm7 chord. Harmonics don’t seem particularly out of the ordinary to us in the present day, but if we go back 30 years the story was very different; although Jaco doesn’t get sole credit for ‘inventing’ the harmonic vocabulary that we have nowadays he was definitely a pioneer of using both natural and false harmonics in order to expand the bass’ ability to convey extended harmony – Jaco totally changed the game with tracks like ‘A Portrait of Tracy’ and ‘Okonkole Y Trompa’ from his self-titled debut, and even managed to integrate them in a singer-songwriter context on Joni Mitchell’s ‘Coyote’.

Voicings like which combine fretted notes with harmonics have become mainstays of the electric bass, and it was Jaco that brought them to our attention.

2. Propulsive 16th note lines

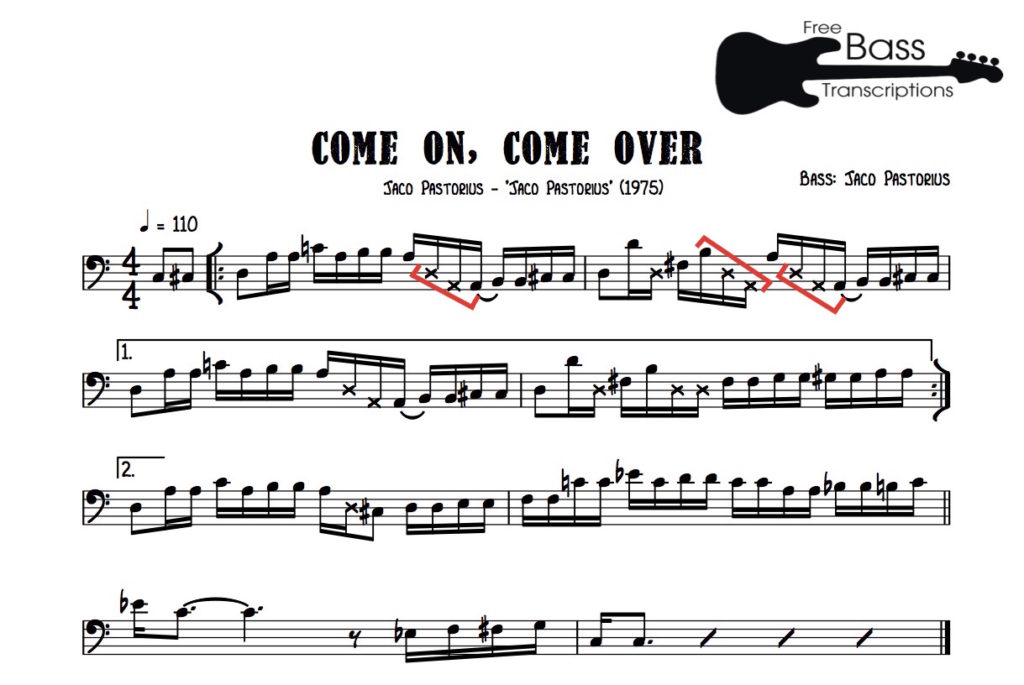

Although Rocco Prestia is widely considered to be the king of relentless 16th note funk grooves – Tower of Power released ‘What Is Hip?’ around the same time as this record came out – Jaco was no slouch either and many of his signature lines, including the chorus to ‘Come On, Come Over’, consist of rapid fire funk motifs interspersed with ghost notes. The 2-bar groove that serves as the main line for this tune is no exception:

Here Jaco begins by outlining the Em7 harmony before descending into open position and using a combination of chord tones and ghost notes to create the rest of the line – he alternates figures on beat 4, first landing on the 5th and then resolving to the open E; this helps to give the groove a more ‘composed’ feeling compared to a constant 1-bar vamp.

Sharp-eyed (and sharp-eared) readers might have spotted that the main groove is almost identical to that of ‘Kuru/Speak Like a Child’ from his debut album, albeit at a slower tempo. The melodic contour of the line is also very similar to that of one of Jaco’s most famous grooves, the chorus of ‘Come on, Come Over’, with the highest note placed on beat 2 of the bar and the introduction of ghost notes in the second half of each bar:

(for a more detailed look at ‘Come On, Come Over’ check out Groove of the Week #34)

3. Chromatic Approach Notes

Another of Jaco’s frequently used trademarks is the chromatic approach, either as a single chromatic approach from a semitone below a chord tone, or a double chromatic approach from a tone below.

These first appear in bars 9 and 10 of the transcription – the sections labelled as ‘chorus’ and ‘bridge’ on the transcription are also littered with these approaches.

Bar 21 of the transcription shows the use of a double chromatic approach at the end of the second verse, where Jaco targets the major 3rd of the D7 chord and uses the open D string to create a double stop:

He would use throughout his later compositions most notably ‘Continuum’.

The chorus figure that uses root- 5th with single chromatic approaches actually hints at the infamous ‘Jaco Samba’ pattern that forms that basis of his lines on ‘(Used To Be A) Cha Cha’ and ‘Invitation’.

4. Rhythmic Displacement

As the song progresses, the verse/chorus/bridge structure gives way to a lengthy, less structured outro section. Here, Jaco leaves his opening groove behind and gives us another great 2 bar vamp that combines propulsive 16th note playing with chromaticism and some simple, yet effective rhythmic displacement:

Displacing the opening of bar 1 ahead by a 16th note transforms this from a stock Em funk groove into something special.

After 12 bars of this, Jaco cranks out a variation on this line that gives a nod towards what would become a cornerstone of his style…

5. Pentatonic Sequencing

Bar 97 of the transcription shows Jaco playing this line:

The first 2 beats are comprised of a minor pentatonic scale sequenced in 4ths and 5ths – after beginning with the root note he plays 4th to flat 7, 5th to root, then 5th to flat 7; This sort of thing was unusual at the time, with most scale sequencing being of the linear variety (typically using consecutive notes in the scale played in 3 or 4 note groupings).

Jaco was one of the first to employ wider interval skips, which became features of his landmark solos including Continuum, Port of Entry and Havona.