‘Don’t Start Now’ was the first of six singles taken from Dua Lipa’s second album, Future Nostalgia (2020). Written as a homage to disco and designed to emulate artists including The Bee Gees and Madonna, it was quite possibly the first song in a decade to make bass players sit up and take notice of something in the Top 40.

Dua Lipa – ‘Don’t Start Now’ bass transcription pdf

Let’s start with the elephant in the room – that bassline is programmed in MIDI rather than played. Does it make it any less valid? I don’t think so. And we still have to get our fingers round it if it appears on a setlist.

Producer Ian Kirkpatrick programmed the bass part using a combination of plugins; Scarbee’s MM-bass (modelled on Bernard Edwards’ sound) for the main line and Spectrasonics’ Trilian for the popped notes. You can also hear a synth doubling the bassline on the third repetition of the verse.

While we’re talking about the popped notes, you’ll notice that there’s no thumb slapping; the groove involves switching between fingerstyle for the lower notes and popping for the octaves. I think of this as ‘half-slap’, and it offers a great alternative to conventional slapping – the bass part jumps out of the mix without becoming overbearing through constant thumping. Some of my favourite half-slap grooves that are transcribed on this site are ‘Treasure’ by Bruno Mars and Jocelyn Brown’s ‘Somebody Else’s Guy’.

‘Don’t Start Now’ Bassline Analysis

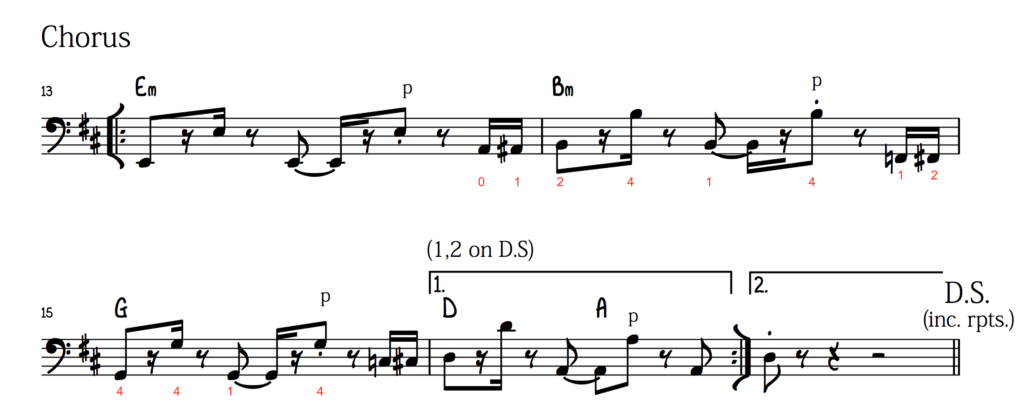

The bassline to ‘Don’t Start Now’ outlines the five-chord verse and chorus harmony (Em – Bm – G – D – A) using two concepts: 16th-note syncopation and double chromatic approach notes. Let’s deal with the rhythmic aspect of things first:

The rhythm in each bar is the same – notice how the only time the bass is on the beat is the downbeat of 1. Every other attack is either on the ‘a’ or the ‘+’ of the beat, which is a sure-fire way to impart a sense of funk to any bass part, while the constant rhythmic repetition ensures that the bassline stays in the listener’s ear. The expensive-sounding, music college term for anything not on the beat is syncopation, which is most likely present in the majority of your favourite basslines.

It’s not just the rhythm that gets repeated in order to make the song catchy – the bass exploits the same harmonic trick of approaching each root note from two semitones lower (known as a double chromatic approach from below). This can be tricky for the fretting hand, as it can leave you unable to reach the octave in time – the fingering above is my preferred method, using the 16th-note rest to allow my fourth finger to jump up and grab the octave. Even though some of the approach notes are non-diatonic (outside the key), 16th notes at 120bpm move quickly enough to make the dissonance acceptable, and the repetitive nature of the line makes the chromaticism even more acceptable. Double chromatic approaches can be found in the parts of some of the great players, including Anthony Jackson and Bernard Edwards.

Speaking of Bernard, we’re looking to emulate his tone here, too. If, like me, you don’t happen to own a Music Man bass (or another brand that sports an MM-style pickup) then you can approximate the bright, ‘burpy’ tone by using the bridge pickup on your jazz bass and bumping the mids. Is it exactly the same sound? No. Will anyone on the gig notice? No.