It seems like there’s been a spate of cases in recent months concerning pop artists being accused of plagiarising existing songs:

- Sam Smith had been listening to too much Tom Petty

- Bruno Mars and Mark Ronson hoped that people had forgotten all about The Gap Band

- Pharell and Robin Thick(e) failed to disguise their love of Marvin Gaye

- Bruno Mars gets called out by Breakbot (personally I hear Earth, Wind & Fire, The Commodores ‘Lady’ and Crown Heights Affair in there too…)

The cliché goes that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, but when does being influenced by an artist become ripping them off? And, more importantly, what does this have to do with this series of blog posts on bass grooves?

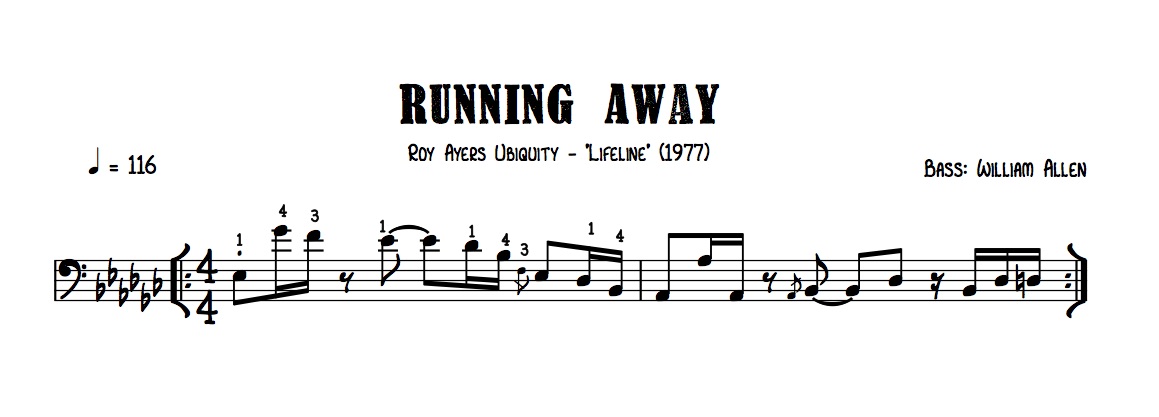

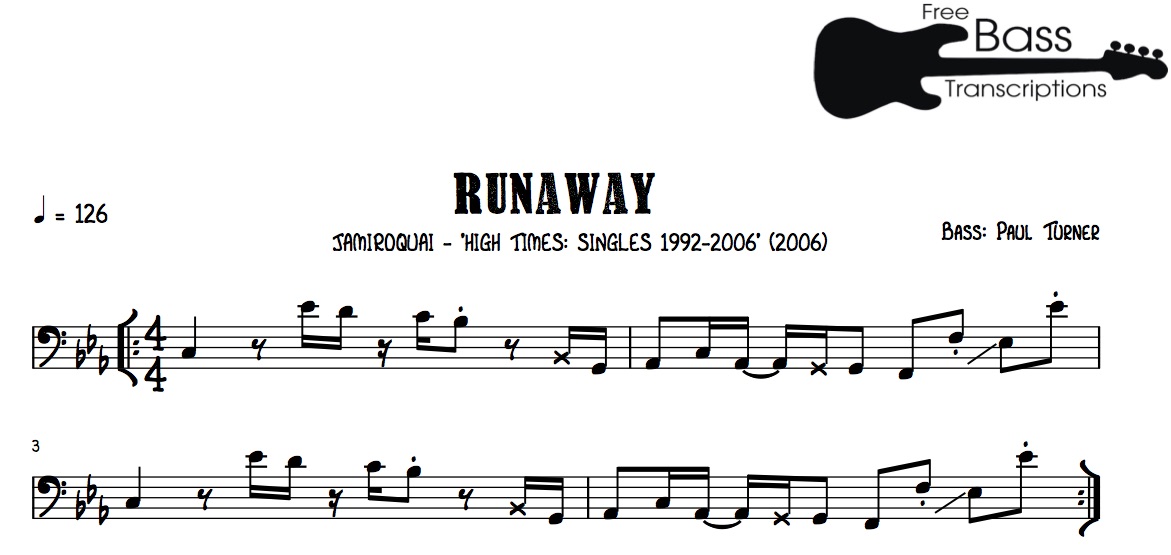

Take a listen to these two grooves – ‘Runaway’ by Jamiroquai and ‘Running Away’ by Roy Ayers:

Sound similar? I certainly think so. If the titles weren’t enough of a giveaway both lines sit at similar tempos and outline their first chord by using root – 10th – descending scale line:

Here are the dots for the main groove of ‘Runaway’ (a full transcription is available here):

So, it’s pretty clear that Paul Turner & co had been listening to a lot of 70s acid jazz, and this should come as no surprise to any of us. Just as nutritionists will tell us that you are what you eat, for musicians it’s a case of you are what you listen to (and what you practise).

If you’ve grown up listening to Herbie Hancock, Lonnie Liston Smith, Roy Ayers and other similar artists then it’s no wonder that the music that you write sounds a certain way – what continues to amaze me is that many of the people that I teach have little or no awareness of ‘tradition’ (understanding who inspired the players that inspire them) and don’t make the connection between what they put in (listening and practise) and what they get out (their playing).

I’ll hold up my hand and admit to being ignorant of many musical things and having wasted lots of time ‘barking up the wrong tree’ in the practice room, but I DO make a concerted effort to understand where the music that means the most to me has come from. This act of delving deeper into the history of the music I love helps to broaden my horizons and provides me with a context in which to view all of the players that inspire me.

What do I mean by all of this? Simply put, you can’t know for certain if you’re being original if you don’t know what came before you. Having a deep knowledge of bass playing ‘traditions’ can help you to identify which traits in your own playing are stolen from external sources and highlight any areas of originality.

Here’s some food for thought which also doubles as a good exercise for anyone who’s asked “How Do I Sound?” or “How Do I Want To Sound?”. Think of it as ‘Bass Player Maths’:

- I find it hard to hear Me’Shell N’degeocello without simultaneously hearing Paul Jackson and Jaco Pastorius

- Listen to Laurence Cottle, then some Pat Metheny (preferably with Michael Brecker). Now listen to Janek Gwizdala. See what I’m getting at?

- Two seemingly opposite influences can produce great results: combine James Jamerson’s chromaticism with Jack Cassidy’s tone and you’re on the way to understanding how Anthony Jackson arrived at some of his concepts.

So go forth and rejoice in becoming a total geek about the music and the bassists that inspire you – I’m willing to bet that your own personal detective work gives you inspiration and insight into what has gone before you and what lies ahead for you.