Five triads types you should know (but most bassists don’t)

Since March 2020, when the UK went into lockdown and all my gigs disappeared overnight, I’ve been teaching people from all over the world about music as it applies to the bass guitar via the magic of Zoom. This is one of my favourite things to do; I love hearing about my students’ musical goals and enjoy the challenge of helping them overcome whatever obstacles might be in their way.

One thing I’ve learned from teaching 500+ Zoom lessons over the last 18 months is that most students – regardless of their age, location, or ability – tend to suffer from the same problems. The most common areas that need to be addressed can be summed up as fundamentals; the basic elements of melody, harmony, and rhythm that need to be bulletproof if we’re to ever have any hope of being musically independent.

Let’s begin with harmony, which is the term that I use to describe anything to do with chords and chord progressions. As bass players, we’re rarely playing chords in the literal sense, but we’re always supporting a chord or chord progression played by another instrument, so it’s vital that we’re comfortable with how chords are constructed and where those notes are on our instrument. More often than not, basslines are made up of arpeggios (the notes of a chord played separately); notes that make up a chord are also known as chord tones.

In the exercises below, you’ll learn the five main arpeggio shapes for bass, along with two different fingerings for each. Having more than one way of playing an arpeggio will help you to access the sound in different areas of the fingerboard.

But what about scales? While scales are important, they contain several ‘weak’ notes that aren’t contained in the chord. I find that students get better results by focusing on arpeggios first because using chord tones really helps to spell out the harmony immediately; every note has a direct correlation to the chord being played by another instrument.

Three is the magic number: Triads

Chords really begin with triads (three-note chords). I like to start by getting students to focus on are the five basic types of triads that occur most frequently in contemporary music:

1. Major

2. Minor

3. Diminished

4. Suspended 4th

5. Augmented

My students often find that once they have a really deep understanding of how these chords are built and how to outline them on the bass then they can apply their knowledge to any style of music that happens to interest them; the rules of harmony remain the same regardless of the style of music that you’re playing.

Let’s delve deeper into each type of triad.

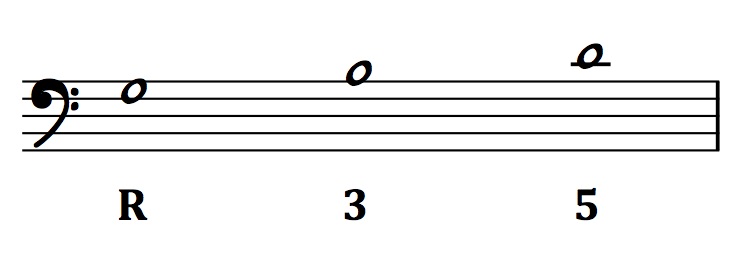

1. Major triads

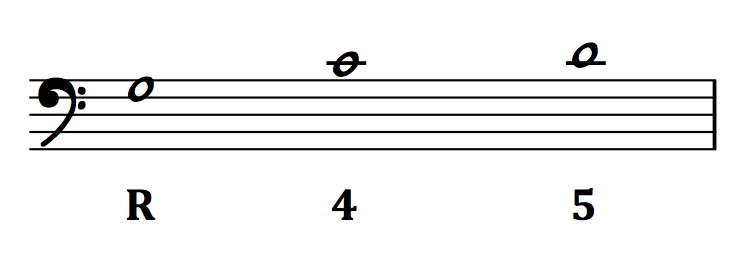

Major triads are built from the root, a major 3rd, and a perfect 5th:

If we analyse the intervals within the triad, we can see that the distance between the root and the major 3rd is four semitones, while the distance between the 3rd and the 5th is three semitones (a minor 3rd), giving a total distance of seven semitones, or a perfect 5th.

Another way of expressing a major triad would be major 3rd + minor 3rd.

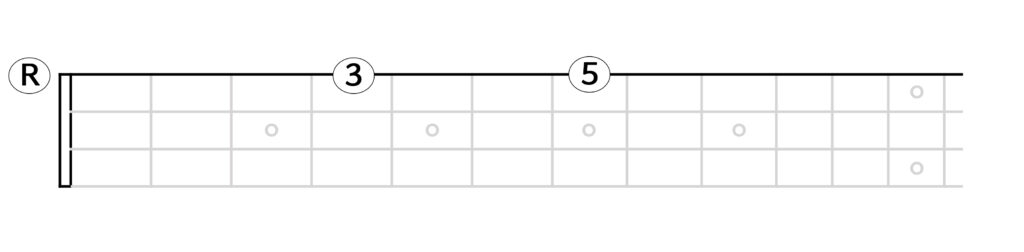

Single string major triads

Played on a single string, a major triad looks like this:

Fingerings for major triads

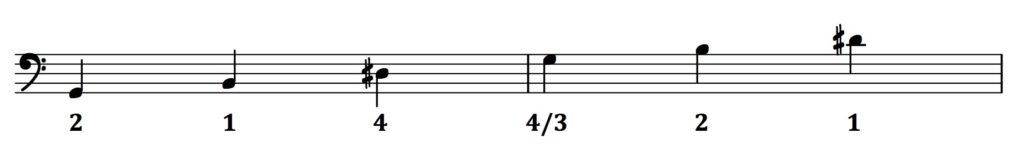

Arranging the chord tones on a single string is great for visualising the sizes of the relative intervals within the triad, but it’s not very useful for most playing situations. We need two practical fingerings for each triad, leading from each ‘half’ of the hand; you’ll see that the first octave begins with finger 2, while the second octave leads with finger 4:

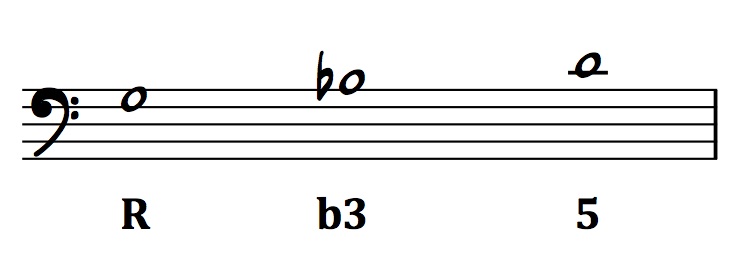

2. Minor triads

A minor triad is built from the root note, a minor 3rd, and a perfect 5th:

Notice that the only difference between the major triad and the minor triad is that the 3rd has been flattened – lowered by a semitone – which completely alters the sound of the triad.

The distance between the root and the 3rd is now only three semitones, which means that the distance between the 3rd and the 5th has increased to four semitones (a major 3rd), which still gives a total distance of seven semitones.

Another way of expressing a minor triad would be minor 3rd + major 3rd

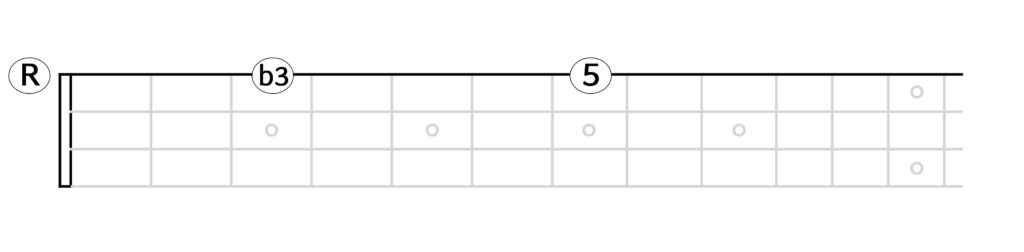

Single string minor triads

Here’s the minor triad on a single string:

Fingerings for minor triads

We’re leading the first octave with finger 1 in order to play the minor 3rd on the same string as the root, which makes things more comfortable for the fretting hand:

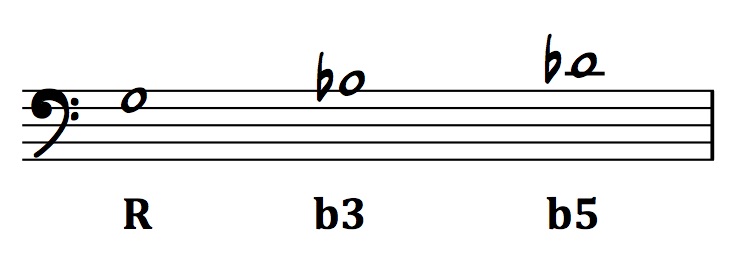

3. Diminished triads

We’ve covered the two possibilities of combining major and minor 3rds, to make major and minor triads but what happens if we use two of the same type of 3rd?

A diminished triad is built by stacking two minor 3rds on top of each other. This results in a rather angular, dissonant sound; although it might not sound great to your ear at first, the diminished triad is found within the major scale and so we need to have ways to get our fingers around it.

Since the total distance has been reduced to six semitones the triad no longer has a perfect 5th. This results in the rather sinister sound of a diminished 5th (also known as a ‘flat 5’ or a ‘tritone’).

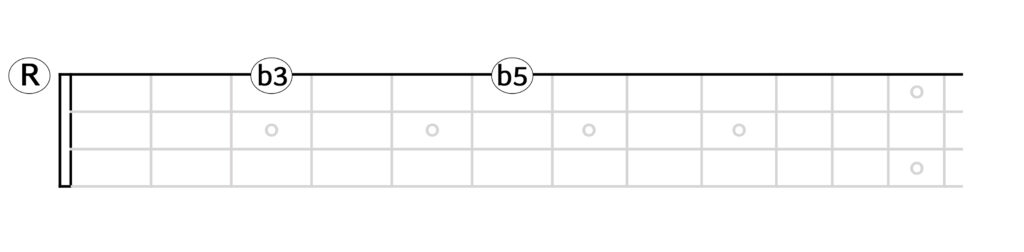

Single string diminished triads

Viewing the diminished triad on a single string allows us to easily see its symmetrical structure:

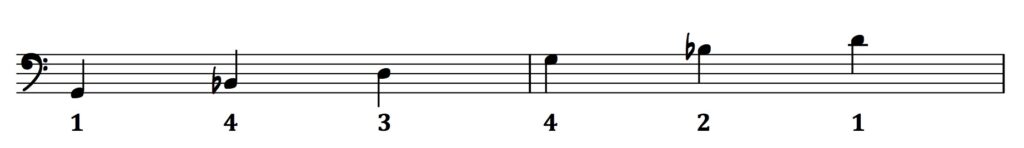

Fingerings for diminished triads

The fingering for the first octave treats the diminished triad as a minor triad with a flattened 5th, with finger two covering the b5. The second octave is one of the few shapes that leads with the third finger; if we attempt to spread the triad over three strings, we soon find that the stretching required makes it impractical for most areas of the fretboard.

4. Suspended triads (sus4)

This is the odd one out in our collection of 3-note chords. In a suspended triad, the 3rd is replaced by another note which creates a suspension. The most common suspended triad is the suspended 4th, or sus4 triad, in which the 3rd is replaced by a perfect 4th:

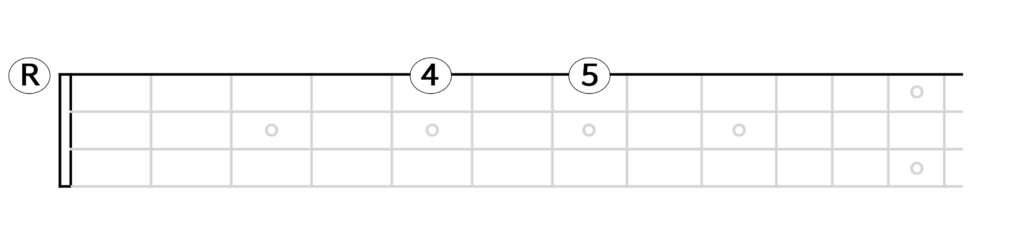

Single string sus4 triads

The single string view of the sus4 triad clearly shows us that instead of a pair of 3rds, we now have a perfect 4th (five semitones) and a major 2nd (two semitones):

Fingerings for suspended triads

Playing perfect 4ths on the bass can be tricky because it involves playing the same fret on two adjacent strings. Here, we’re working on two ways of dealing with 4ths; in the first octave, the index finger on the fretting hand is going to ‘roll’ onto the A-string, fretting the 4th with the bottom part of the first finger joint. In the second octave, we’re using two different fingers to deal with the interval of a 4th:

5. Augmented triads

The augmented triad doesn’t occur naturally within the major scale – they can be found in the melodic minor, harmonic minor, and whole tone scales – but it’s a sound and a structure that we need to be familiar with if we’re to become well-rounded musicians. Augmented triads are symmetrical and are made by combining two major 3rds.

As with the diminished triad, the distance between the root and the 5th is no longer perfect, which gives the triad much more colour. Here, the interval between the root and 5th is larger (eight semitones; think about the meaning of the word augment), resulting in an augmented 5th, commonly referred to as ‘sharp 5’:

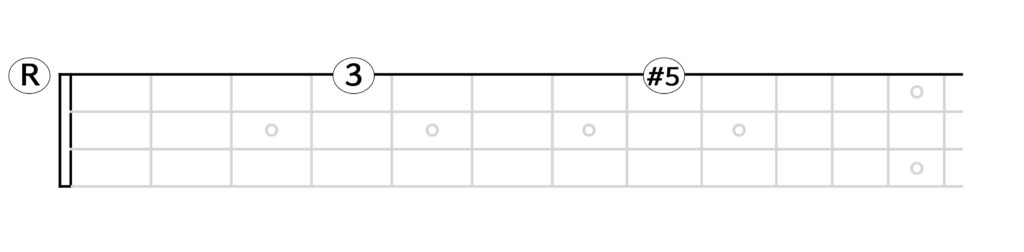

Single string augmented triads

Again, laying out the triad on a single string allows us to see its symmetrical structure clearly:

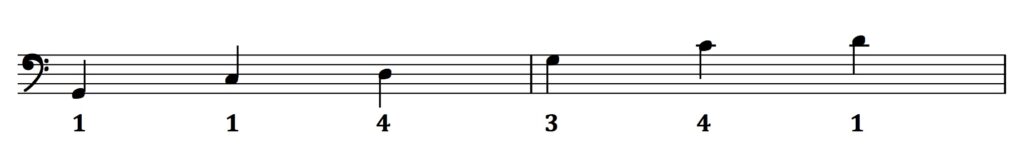

Fingerings for augmented triads

The first octave treats the augmented triad as a major triad with a #5 (which is exactly what it is!); remember to use your fretting hand thumb to help move up the neck rather than stretching the fingers to reach the #5:

How to practice triad arpeggios on the bass

Now that we’ve covered the most common possibilities of triads that you might encounter it’s time to start drilling them until they become second nature.

1. Parallel arpeggio practice

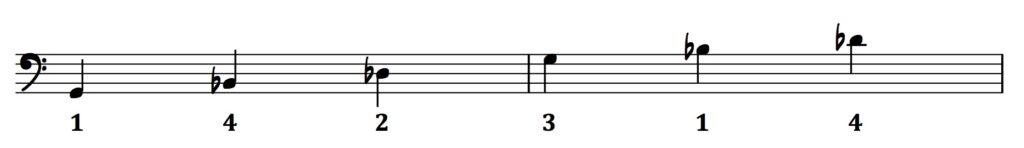

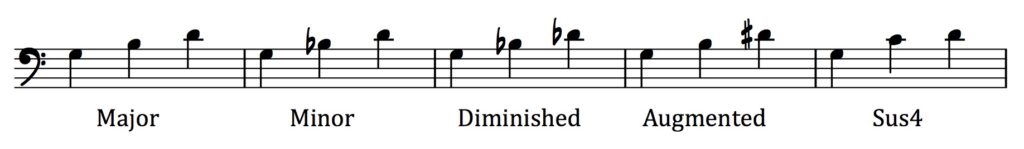

The first step is to run the five arpeggios from the same root note (this is known as playing them in parallel):

For each chord type, make sure that you’re comfortable with these three ideas:

- The intervals that make up the triad

- The pitch names

- The fingerings

Once you can run each triad in parallel across two octaves while being conscious of the intervallic structure and individual pitch names it’s time to move to the next step, derivative practice.

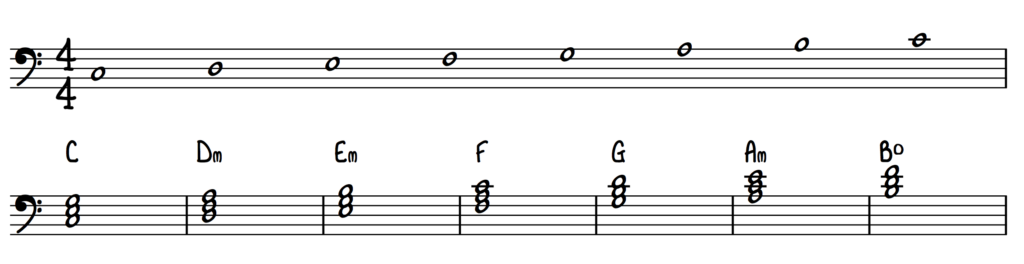

2. Diatonic arpeggio practice

More often than not, we’re playing triads that have been derived from a scale; these are also known as diatonic triads (diatonic simply means using the notes of the scale or key). If we take a major scale and build triads from each scale degree we always get the same sequence of chords. If we harmonise (build chords from) a C major scale, we get the following arrangement of triads:

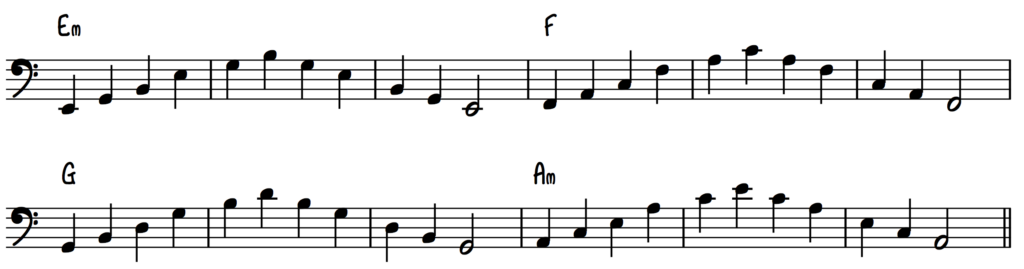

We can then use this sequence of chords as a blueprint for practising our two-octave triads. Starting on the lowest possible triad in the key (E minor for those playing a 4-string bass, B diminished for anyone with a B-string) and moving horizontally along the lowest string of the bass, we can practise the diatonic arpeggios of C major as follows:

For this exercise, continue to play through the next triad in the sequence until you run out of frets, then work your way back down again. Not challenging enough? Change the key each time you start the exercise!

Working on these triad arpeggios will develop your musical awareness in a number of ways:

- Learning specific fingerings for arpeggios means that your fingers always know how they’re going to deal with a set sequence of notes, which reduces the number of mistakes you’ll make when creating basslines on the fly

- Playing through common triad types is great ear training, as you’re familiarising yourself with the sound of different chord types. This will improve your ability to pick out chord progressions and basslines by ear